Accountable Talk

Definition

Accountable Talk refers to talk that is meaningful, respectful, and mutually beneficial to both speaker and listener.

Accountable talk stimulates higher-order thinkinghelping students to learn, reflect on their learning, and communicate their knowledge and understanding.

Basic Assumptions and Principles

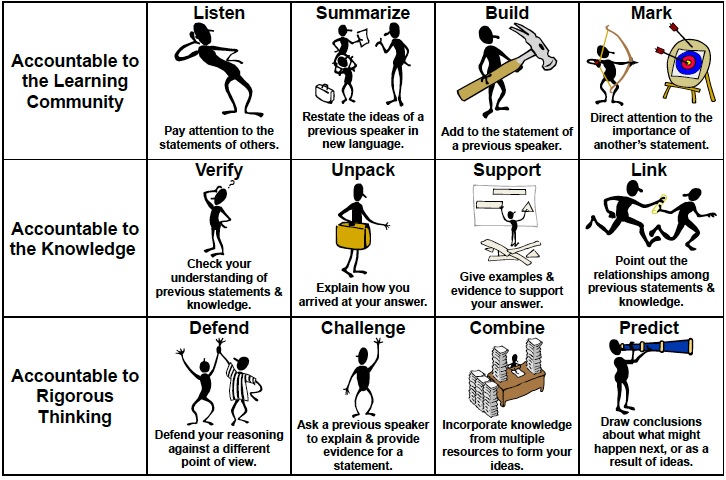

Accountability to the Learning Community

1. Students actively participate in classroom talk.

- Each student is able to participate in several different kinds of classroom talk activities.

- Students’ talk is appropriate in tone and content to the social group and setting and to the purpose of the conversation.

- Students allow others to speak without interruption.

- Students speak directly to other students on appropriate occasions.

2. Students listen attentively to one another.

- Students’ body language/eye contact show attention.

- When appropriate, students make references to previous speakers.

- Speakers’ comments are connected to previous ideas.

- Participants avoid inappropriate overtalk.

- Participants’ interest is in the whole discussion, not only in their own turn taking.

3. Students elaborate and build upon ideas and each others’ contributions.

- Talk remains related to text/subject/issue.

- Related issues or topics are introduced and elaborated.

- Talk is about issues rather than participants.

4. Students work toward the goal of clarifying or expanding a proposition.

- Students revoice, summarize, paraphrase each other’s argument(s)

- Students make an effort to ensure they understand one another.

- Students clarify or define terms under discussion.

Accountability to Knowledge

1. Students make use of specific and accurate knowledge.

- Students make specific reference to a text to support arguments and assertions.

- Students make clear reference to knowledge built in the course of discussion.

- Examples or claims using outside knowledge are accurate, accessible, relevant.

2. Students provide evidence for claims and arguments.

- Unsupported claims are questioned and investigated by discussion participants.

- Requests are made for factual information, elaboration, rephrasing and examples.

- Students call for the definition and clarification of terms under discussion.

- Students challenge whether the information being used to address a topic is relevant to the discussion.

3. Students identify the knowledge that may not be available yet which is needed to address an issue.

Accountability to Rigorous Thinking

1. Students make use of specific and accurate knowledge.

- Students refer to a variety of texts as sources of information.

- Students connect ideas within and between texts.

- Students use previous knowledge to support ideas and opinions.

2. Students construct explanations.

- Students acknowledge that more information is needed.

- Students use sequential ideas to build logical and coherent arguments.

- Students employ a variety of types of evidence.

3. Students formulate conjectures and hypotheses.

- Students use “what if” scenarios as challenging questions or supporting explanations.

- Students formulate hypotheses and suggest ways to investigate them.

- Students indicate when ideas need further support or explanation.

4. Students test their own understanding of concepts.

- Students redefine or change explanations.

- Students ask questions that test the definition of concepts.

- Students draw comparisons and contrasts among ideas.

- Students identify their own bias.

- Students indicate to what degree they accept ideas and arguments.

5. Classroom talk is accountable to generally accepted standards of reasoning.

- Students use rational strategies to present arguments and draw conclusions.

- Students provide reasons for their claims and conclusions.

- Students fashion sound premise-conclusion arguments.

- Students use examples, analogies, and hypothetical “what if” scenarios to make arguments and support claims.

- Students partition argument issues and claims in order to address topics and further discussion.

6. Students challenge the quality of each other’s evidence and reasoning.

- The soundness of evidence and the quality of premise-conclusion arguments are assessed and challenged by discussion participants.

- Hidden premises and assumptions of students’ lines of argument are exposed and challenged.

- Students pose counter-examples and extreme case comparisons to challenge arguments and claims.

7. Classroom talk is accountable to standards of evidence appropriate to the subject matter.

Source: http://image.slidesharecdn.com/classdiscussionguidelines-110710164938-phpapp01/95/class-discussion-guidelines-1-728.jpg?cb=1310334608

Classroom Implication and Teaching Strategies

To promote accountable talk, teachers create a collaborative learning environment in which students feel confident in expressing their ideas, opinions, and knowledge.

Accountable Talk practices are not something that spring spontaneously from students’ mouths. It takes time and effort to create an Accountable Talk classroom environment in which this kind of talk is a valued norm. It requires teachers to guide and scaffold student participation.

Teachers create Accountable Talk norms and skills in their classrooms

- by modeling appropriate forms of discussion and

- by questioning, probing, and leading conversations.

For example, teachers may

- press for clarification and explanation,

- require justifications of proposals and challenges,

- recognize and challenge misconceptions,

- demand evidence for claims and arguments, or

- interpret and “revoice” students’ statements.

Over time, students can be expected to carry out each of these conversational “moves” themselves in peer discussions. Once the norms for conversation within the classroom have been established, academically productive talk is jointly constructed by teachers and students, working together towards rigorous academic purposes in a thinking curriculum.

Features of Accountable Talk

Accountability to the Learning Community

- Careful listening to each other

- Using and building on each others ideas

- Paraphrasing and seeking clarification

- Respectful disagreement

- Using sentence stems

Accountability to Accurate Knowledge

- Being as specific and accurate as possible

- Resisting the urge to say just anything that comes to mind.

- Getting the facts straight

- Challenging questions that demand evidence for claims

Accountability to Rigorous Thinking

- Building arguments

- Linking claims and evidence in logical ways

- Working to make statements clear

- Checking the quality of claims and arguments

References

Alexander, R.J. (2001). Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education. Boston: Blackwell.

Alexander, R.J. (2004). Talking to Learn. TES Magazine. January 30, 2004, 1-4.

Chapin, S., OConner, C. & Anderson, A. (2003). Classroom Discussions: Using Math Talk to Help Students Learn Grades 1-6. Sausalito, C: Math Solutions.

Michaels, M., O’Conner, C. & Resnick, L. (2007). Deliberative Discourse Idealized and Realized: Accountable Talk in the Classroom and in Civic Life. Studies in Philosophy and Education 7. 283-297.

Rowe, M. (1986). Wait Time: Slowing Down May Be a Way of Speeding Up! Journal of Teacher Education 37(1) 43-50.

West, L. (2011). Descriptive Feedback Presentation to Toronto District School Board. March 23, 2011.

Resources

How does Accountable Talk® promote learning?

Interview video: http://ifl.lrdc.pitt.edu/index.php/resources/ask_the_educator/lauren_resnick

Bringing Close Reading and Accountable Talk into an Interactive Read Aloud of Gorillas (3-5)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nznO1BMtahw

Key Works

Resnick, L. B., Pontecorvo, C., & Säljö, R. (1997). Discourse, tools, and reasoning: Essays on situated cognition (pp. 1-20). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Michaels, S., OConnor, C., & Resnick, L. B. (2008). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: Accountable talk in the classroom and in civic life.Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27(4), 283-297.