- Overview

- Concept Mapping

- Reading to Learn

- Inquiry-Based Learning

- Problem-Based Learning

- Knowledge Building

- Learning Journals

Learning Journals

Learning journal as a means to foster metacognition

Miss Cheung has been using the science learning journal as a means to develop students metacognition by engaging them in scientific inquiry inside and outside the classroom. The journal is a collection of a students science-related learning experience, such as his/her proposed solutions to a problem, summary notes of lessons, science issues encountered in the media and daily life, results of an internet search for a self-study topic, home investigations and reflections. To motivate her students to take ownership of the journal, Miss Cheung encourages them to use their own language and preferred styles of presentation, so each learning journal is unique and personal.

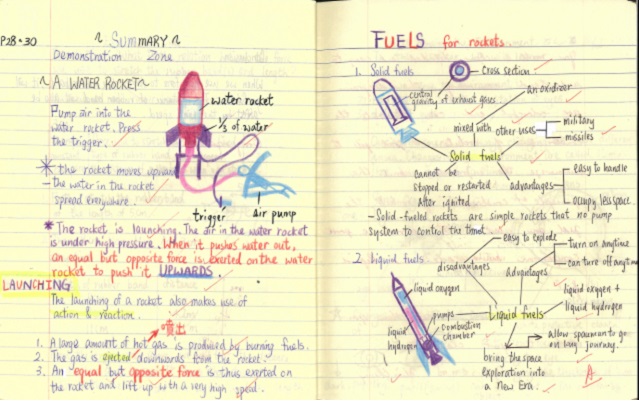

Figure 1: Excerpt from a students science journal in which she summarized what she had learned about rockets.

The student, Ching, used point form, drawings and a mind map to summarise her understanding of the mechanics in launching a rocket, and compared two types of fuels used by rockets. Miss Cheung thanked Ching for her devoted work and was going to show it to the class to inspire the rest of the students. It is not common for a teacher to thank students personally for their good effort in a traditional classroom. The use of a journal allows the teacher to track individual students learning progress and provides a channel for personal communication between her and the student.

According to the topic the students are learning, Miss Cheung assigns some investigative tasks for them to carry out at home, such as observing and recording an egg which is put into vinegar, investigating factors affecting the rate of the turning brown of an apple, preparing natural indicators from plants and testing them on household substances, etc. Miss Cheung just explains the aims of the task and the students are given a free hand to explore in their own ways. They will record their thoughts about designing the experiment, what they have done, what was found, their discussion about the limitations of the design and their reflections in the journals. Most of all, the journal is not just a descriptive account of what the students did, but a platform for sharing their thinking processes: how and why they did what they did, and what they think about what they did.

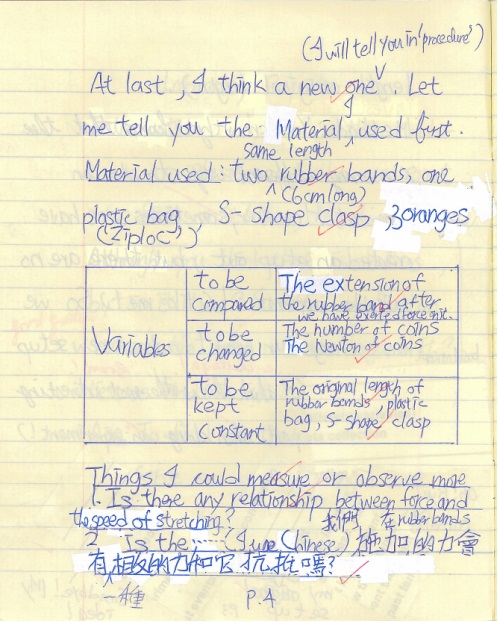

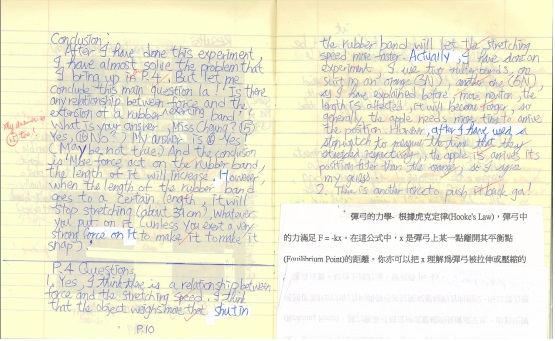

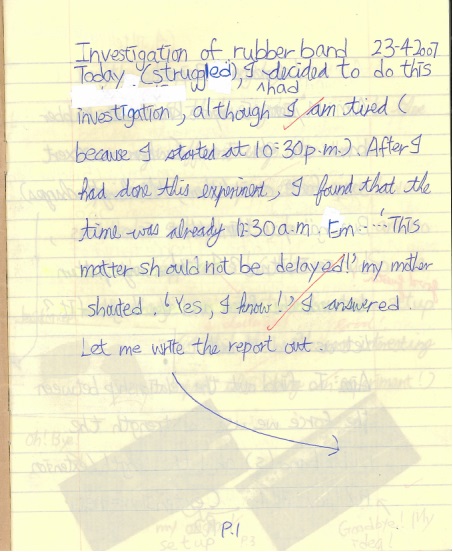

Figure 2: Excerpt from a students science journal reporting a home investigation.

Instead of presenting the typical format of a science report, the student, Chun, documented his investigation in the form of a narrative. He felt safe to express his feelings because he had been enjoying a great deal of autonomy in organising his work.

In his own words, Chun introduced the aim of the investigation in the form of a question to look for patterns between two variables, which is what essentially most, if not all, scientific investigations are about. Miss Cheung acknowledged the clear direction of Chuns investigation by highlighting it and giving positive feedback.

The lack of laboratory apparatus at home challenged Chun to improvise creatively. He went through what early scientists had experienced and had enjoyed this problem-solving process and found it to be fun.

Here, Chun began to use the terminology in writing a science report (procedure, material, prediction…). He also defined the variables involved in a quantitative manner.

When he ran out of his English language resources, Chun resorted to his mother tongue (Chinese). He was fully aware of this improper switch but was not going to let a language barrier prevent him from expressing his thoughts. Miss Cheung, instead of correcting this mixed use of language, simply put a tick over it, respecting Chuns enthusiasm in investigation and his dynamic language use.

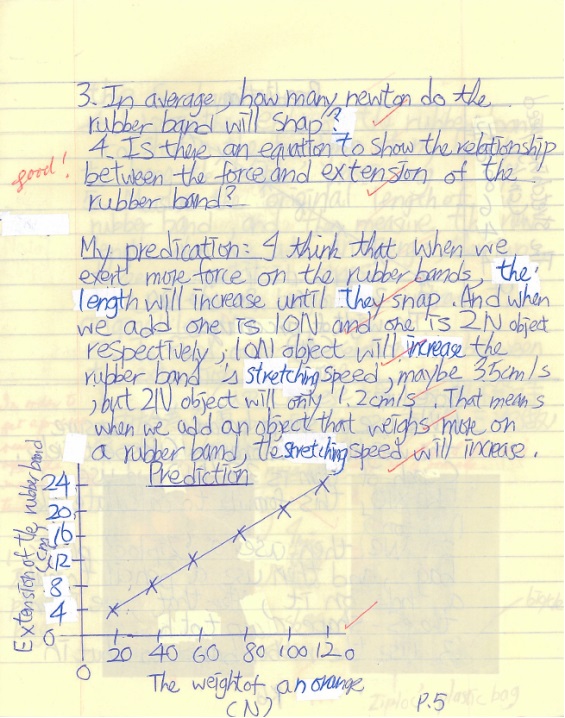

Chun defined his research question further in measurable terms. The attempt to look for patterns in terms of an equation reflected that Chun was beginning to think like a scientist.

Making a prediction before carrying out an investigation prepares ones mind for deciding what actions to take, what measurements to make and what to look for. Chun had made his prediction in detail using imaginary figures, and had put them in a graphical presentation for easy understanding. Writing a journal keeps the author responsible for the readers understanding, developing his ability to think from someone elses perspective.

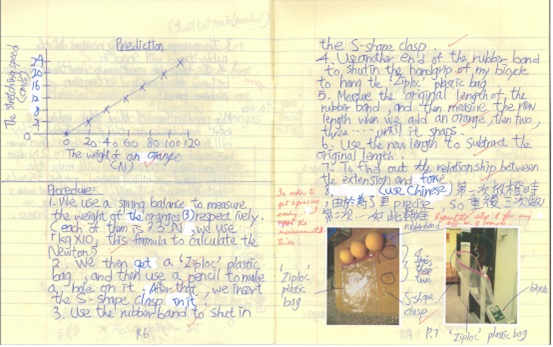

At the start, Chun reported what he did in the first person by using We…, and then migrated to using imperative clauses as in a typical science report. Keeping the journal allowed him to proceed at his own pace.

Chun improvised oranges as weights. Noting that the oranges were not identical, he repeated his experiment three times in each case. But Chun could not express himself in English and resorted to Chinese. Miss Cheung valued his ideas and showed him how to say it in English.

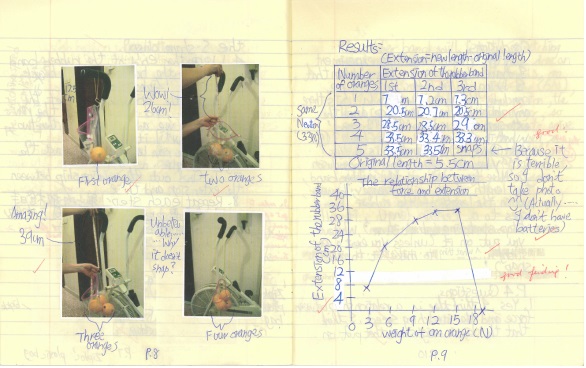

Chun shared his wonderment and the questions in his mind as he performed his experiment – a sign of metacognitive awareness.

Chun used the colloquial Cantonese particle la! at the end of a sentence to add conversational sense as if he was talking face-to-face with Miss Cheung. By asking his teacher to guess his conclusion, Chun tried to engage her in his investigation.

The investigation had motivated Chun to move beyond describing patterns in data. He searched for what scientists know about the phenomenon and learned about Hooks Law (a senior form physics topic) by himself. This is an example of self-directed learning. The colloquial Cantonese particle ar! at the end of I understand revealed how excited he was when he found himself able to understand Hooks law.

A learning journal may also be called a learning log, a fieldwork diary or a personal development planner, taking any form like a notebook, a blog or even an audio record. The essence is, it gives a live picture of a students growing understanding of a subject experience and what he/she thinks about and responds to the experience. Being able to reflect, monitor and regulate ones learning experience and thinking process is crucial to independent and life-long learning. The examples of Miss Cheungs class demonstrated how keeping a learning journal allows the students to explore creatively and freely at their own paces while developing their metacognitive skills over time.

Suggestions for Teacher Workshop: You may want to show teacher participants the learning journal without the comments and ask them to discuss what they think, perhaps focusing on areas of metacognition and self-regulated learning. Miss Cheungs comments can then be shown for further discussion.