Teacher-Student Relationship

Definition

The nature and quality of childrens relationships with their teachers play a critical and central role in motivating and engaging students to learn.

Teacher-student relationships are typically defined with respect to emotional support as perceived by the student and examined with respect to their impact on student outcomes. (Wentzel, 2009)

Basic Assumptions and Principles

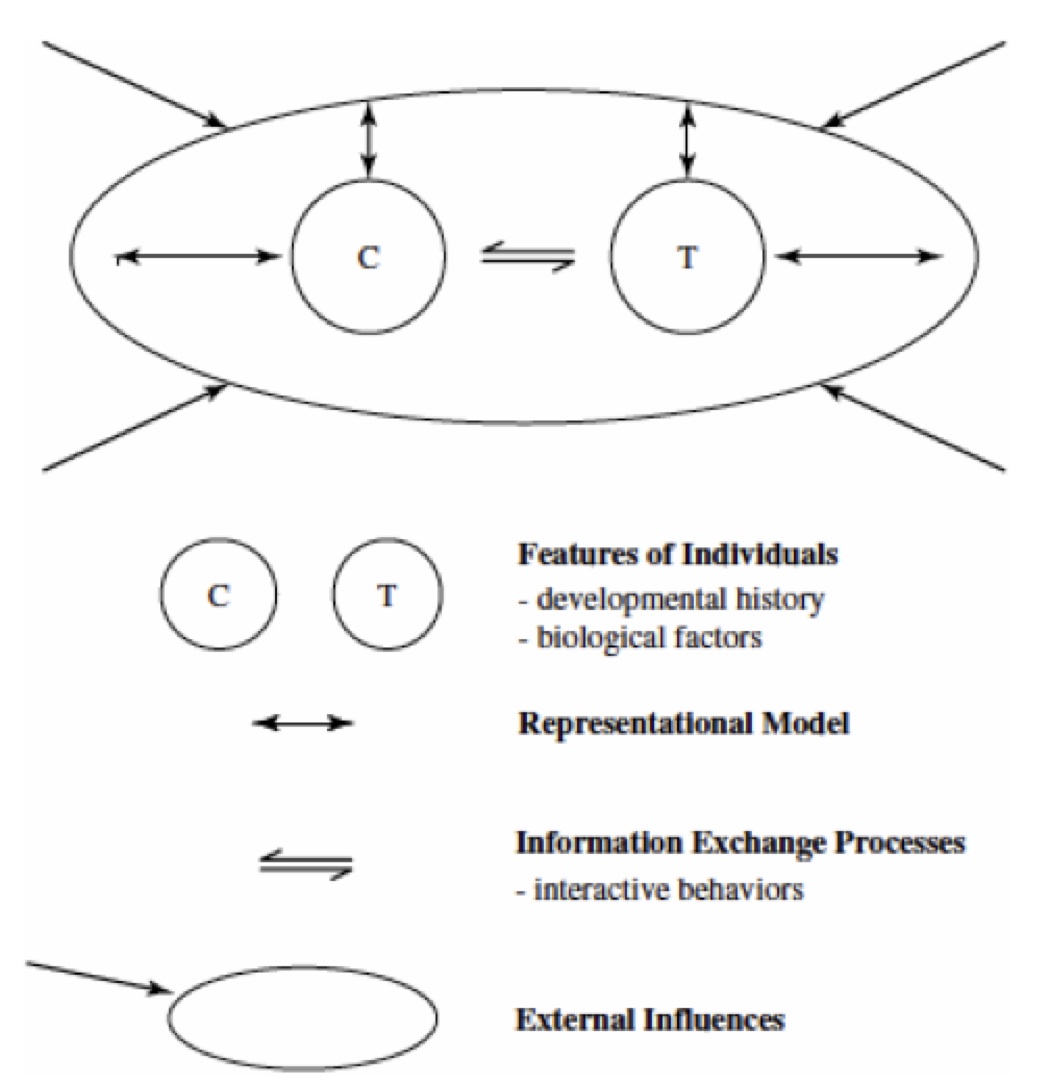

A Conceptual Model of Child-Teacher Relationships

Figure 1. Source: Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. Handbook of psychology

A conceptual model of child-teacher relationships is presented in the Figure above. As depicted in the Figure, the primary components of relationships between teachers and children are

- features of the two individuals themselves,

- each individuals representation of the relationship,

- processesby which information is exchanged between the relational partners

- external influences of the systems in which the relationship is embedded.

The current model places more emphasis on the partners representations of the relationship as distinct from characteristics of the individuals

Classroom Implication and Teaching Strategies

Effective teachers are typically described as those

- who develop relationships with students that are emotionally close, safe, and trusting,

- who provide access to instrumental help

- who foster a more general ethos of community and caring in classrooms.

(Wentzel, 2012)

What do positive student-teacher relationships look like in the classroom?

- Teachers show their pleasure and enjoyment of students.

- Teachers interact in a responsive and respectful manner.

- Teachers offer students help (e.g., answering questions in timely manner, offering support that matches the children’s needs) in achieving academic and social objectives.

- Teachers help students reflect on their thinking and learning skills.

- Teachers know and demonstrate knowledge about individual students’ backgrounds, interests, emotional strengths and academic levels.

- Teachers seldom show irritability or aggravation toward students.

Dos and Don’ts

Do

- Make an effort to get to know each student in your classroom. Always call them by their names and strive to understand what they need to succeed in school (Croninger & Lee, 2001).

- Make an effort to spend time individually with each student, especially those who are difficult or shy. This will help you create a more positive relationship with them (Pianta, 1999; Rudasill, Rimm-Kaufman, Justice, & Pence, 2006).

- Be aware of the explicit and implicit messages you are giving to your students (Pianta, et al., 2001; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002). Be careful to show your students that you want them to do well in school through both actions and words.

- Create a positive climate in your classroom by focusing not only on improving your relationships with your students, but also on enhancing the relationships among your students (Charney, 2002; Donahue, Perry & Weinstein, 2003).

Don’t

- Don’t assume that being kind and respectful to students is enough to bolster their achievement. Ideal classrooms have more than a single goal: in ideal classrooms, teachers hold their students to appropriately high standards of academic performance and offer students an opportunity for an emotional connection to their teachers, their fellow students and the school (e.g., Gregory & Weinstein, 2004; McCombs, 2001).

- Don’t give up too quickly on your efforts to develop positive relationships with difficult students. These students will benefit from a good teacher-student relationship as much or more than their easier-to-get-along-with peers (Baker, 2006; Birch & Ladd, 1998).

- Don’t assume that respectful and sensitive interactions are only important to elementary school students. Middle and high school students benefit from such relationships as well (Croninger & Lee, 2001; Meece, Herman, & McCombs, 2003; Wentzel, 2002). Don’t assume that relationships are inconsequential. Some research suggests that preschool children who have a lot of conflict with their teachers show increases in stress hormones when they interact with these teachers (Lisonbee, Mize, Payne, & Granger, 2008).

Resources

Improving Students’ Relationships with Teachers to Provide Essential Supports for Learning

http://www.apa.org/education/k12/relationships.aspx?item=1

References

- Quintana, C., Shin, N., Norris, C., & Soloway, E. (2006). Learner-centered design: Reflections on the past and directions for the future. In R. K. Sawyer (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 119-134), Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. Handbook of psychology.

- Wentzel, K. R. (2012). Teacher-Student Relationships and Adolescent Competence at School. In Interpersonal Relationships in Education (pp. 19-35). Sense Publishers.

- The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences ?Chapters

- Quintana, C., Shin, N., Norris, C., & Soloway, E. (2006). Learner-centered design: Reflections on the past and directions for the future. In R. K. Sawyer (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 119-134), Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.