Situated and Exp Learning

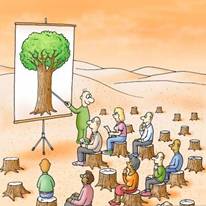

Figure 1. Source: http://lowres.cartoonstock.com/environmental-issues-tree-deforestation-forests-rainforests-rain_forests-sea0860_low.jpg

Freddie is a teacher who teaches environmental issues at school. To enhance students learning, he organized an excursion trip to Europe for his students who get a chance to observe the environment measures and visit the factory of wind turbines there. Students will also need to complete a small group project to investigate the pollution problem in Hong Kong and come up with feasible measure after the excursion. This enables his students to connect what they have learned in school with what they observed in Europe and apply their knowledge to the group project. The strategy that Freddie employed in the above case is called situated learning and please find out more about this strategy in the paragraphs below.

Definition

As it is closely related to socio-culturalism, situated learning emphasized the idea that much of what is learned in specific to the situation in which it is learned (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Basic Assumptions and Principles

According to Brown et al. (1989), meaningful learning will only take place if it is embedded in the social and physical context within which it will be used. Therefore,

-

Knowledge is situated, being in part a product of the activity, context, and culture in which it is developed and used.

-

Learning is doing which occurs when students work on authentic tasks that take place in real-world setting (Winn, 1993).

Central to the perspectives of situated learning is the belief that (Barab & Duffy, 2000)

-

Knowing is an activity-not a thing;

-

Knowing is always contextualized-not abstract;

-

Knowing is reciprocally constructed in the individual-environment interaction-not objectively defined or subjectively created; and

-

Knowing is a functional stance on the interaction-not a ‘truth’.

Primary Theorist:

Jean Lave

Figure 1. Jean Lave

Source: http://activelearner.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/jean-lave_small.jpg

In contrast with most classroom learning activities that involve abstract knowledge which is and out of context, Lave argues that

-

Learning is situated

-

Learning is embedded within activity, context and culture

-

Learning is also usually unintentional rather than deliberate

Her work has been instrumental in providing the research base for the situated learning theory, including the now widely adopted concepts of

1. legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1999)

Learner inevitably participate in communities of practitioners and that the mastery of knowledge and skill requires newcomers to move toward full participation in the sociacultural practices of a community.

2. communities of practice

A community of practice is a collection of people who engage on an ongoing basisin some

common endeavor. Communities of practice are everywhere and that we are generally involved in a number of them – whether that is at work, school, home, or in our civic and leisure interests.

According to Wenger (1998), a community of practice defines itself along three dimensions:

-

What it is about its joint enterprise as understood and continually renegotiated by its members.

-

How it functions – mutual engagement that bind members together into a social entity.

-

What capability it has produced the shared repertoire of communal resources (routines, sensibilities, artefacts, vocabulary, styles, etc.) that members have developed over time.

Classroom Implication and Teaching Strategies

Four claims of situated learning identified in a report of the National Research Council (Reder & Klatzky, 1994)

-

Action is grounded in the concrete situation in which it occurs.

-

Knowledge does not transfer between tasks.

-

Training by abstraction is of little use.

-

Instruction needs to be done in complex, social environments.

Herrington and Oliver (1995) propose a model of instruction based on situated learning to be used in the design of learning environments.

-

Provide authentic context

Context should reflect the way the knowledge will be used in real-life including the complexity of the real-world situation, providing purpose and the possibility for extended exploration.

-

Provide authentic activities

Activities should be ill-defined demanding that learners ‘find’ and ‘solve’ problems inherent in the situation and determine how they will accomplish the task.

-

Provide access to expert performances and the modelling of processes

-

Provide multiple roles and perspectives

Providing the learner with multiple opportunities to engage in an activity from differing perspectives will reveal different aspects of the situation.

-

Support collaborative construction of knowledge

Activities should encourage collaborative searches for suggestions and solutions to promote critical thinking.

-

Provide coaching and scaffolding at critical times

The learning environment should be available to intercept and offer hints and strategies when learners are unable to progress in the task.

-

Promote reflection to enable abstractions to be formed

The environment presentation of problems should require that the learner take the entire environment or situation into consideration when problem solving. In contrast to Mastery learning, a linear path through the content that is presented in isolated component is discouraged.

-

Promote articulation to enable tacit knowledge to be made explicit

Lave and Wenger (in Herrington and Oliver, 1995) Articulation of the vocabulary and the stories of a culture of practice that is an integral part of the situation presented within the learning environment deepen a learner’s understanding of a topic.

-

Provide for integrated assessment of learning within the tasks

Assessment and feedback on a learner’s progress and during tasks should be offered without resorting to tests.

Resources

The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences ?Chapters?

Greeno, J. (2006). Learning in activity. In R. K. Sawyer (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 79-96), Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

NAPLeS Webinar Series by Jim Greeno and Tim Nokes: Situated cognition

(http://isls-naples.psy.lmu.de/intro/all-webinars/greeno-nokes/index.html)

Presentation Slides: Situative Cognition

(http://isls-naples.psy.lmu.de/intro/all-webinars/greeno-nokes/slides_greeno-nokes.pdf)

Required Reading

Engle, R. A. (2006). Framing interactions to foster generative learning: A situative account of transfer in a community of learners classroom. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15, 451-498.

[Online](http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15327809jls1504_2#.U6u2Y5SSyFU)

Nokes-Malach, T. J., & Mestre, J. (2013). Toward a model of transfer as sense-making. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 184-207.

[Online](http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00461520.2013.807556#.U6u6JZSSyFU)

van de Sande, C. C. & Greeno, J. G. (2012). Achieving alignment of perspectival framings in problem-solving discourse. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21, 1-44.

[Online](http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10508406.2011.639000#.U6u775SSyFU)

Key Works

-

Anderson, J. R., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (1996). Situated learning and education. Educational researcher, 25(4), 5-11.

-

Brown, J.S., Collins, A. & Duguid, S. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

-

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in Practice: Mind, mathematics, and culture in everyday life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

-

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1990). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Successful Examples

- Situated Learning and Communities of Practice Video

- Everyday Life and Learning with Jean Lave

- http://www.youtube.com/embed/FAYs46icCFs

- Jean Lave: What is Learning? and Why should we Care?

References

-

Brown, J.S., Collins, A. and Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-41.

-

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. (2000). From practice fields to communities of practice. In D. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (pp. 25-56). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

-

Herrington, J. and Oliver, R. (1995) Critical Characteristics of Situated Learning: Implications for the Instructional Design of Multimedia. in Pearce, J. Ellis A. (ed) ASCILITE95 Conference Proceedings (253-262). Melbourne: University of Melbourne

-

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

-

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1999). Legitimate peripheral participation. Learners, learning and assessment, London: The Open University, 83-89.

-

Reder , L. M. , & Klatzky , R. L. ( 1994 ). Transfer: Training for performance. In D. Druckman

-

& R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Learning, remembering, believing: Enhancing human performance (pp. 2556). Washington, DC : National Academy Press .

-

Wenger, E. (1998) ‘Communities of Practice. Learning as a social system’, Systems Thinker,

-

http://www.co-i-l.com/coil/knowledge-garden/cop/lss.shtml. Accessed December 30, 2002

-

Winn, W. (1993). A constructivist critique of the assumptions of instructional design. In T. M. Duffy, J. Lowyck, & D. H. Jonassen (Eds.), Designing environments for constructive learning (pp. 189-212). Berlin: Springer-Verlag