Learning Communities

Definition

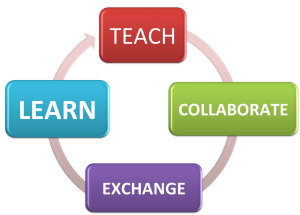

The model of situated learning proposed that learning involved a process of engagement in a ‘community of practice’:

-

be groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly

-

be everywhere, for instance at work, school, home, or in our civic and leisure interests

-

be usually unintentional rather than deliberate and continues after graduation.

Figure 1. source: http://vet-education.org/welcome/?tag=learning

Basic Assumptions and Principles

There are three required components of community of practice:

-

There needs to be a domain. Its not just a network of people or club of friends. Membership implies a commitment to the domain.

-

There needs to be a community. A necessary component is that members of a specific domain interact and engage in shared activities, help each other, and share information with each other. They build relationships that enable them to learn from each other.

-

There needs to be a practice: A CoP is not just people who have an interest in something (e.g. sports or agriculture practices). The third requirement for a CoP is that the members are practitioners. They develop a shared repertoire of resources which can include stories, helpful tools, experiences, stories, ways of handling typical problems, etc. This kind of interaction needs to be developed over time.

Classroom Implication and Teaching Strategies

In formal education, issues related to community of practice are not uncommon:

-

“Classroom dynamics”, “class spirit”, etc. refer to similar issues

-

Instructional designs like the knowledge-building community model (with its computer supported intentional learning environments) depend very much on the emergence of community practices.

-

Various forms of project-oriented learning, etc. also aim to engage learners as members of a community of practice.

Wenger points out 5 activities crucial to building a CoP. (Wenger, 1988, p. 232)

-

Events that bring the community together.

-

Connectivity through various contexts and media.

-

Membership that is neither so extended that its focus is diluted or that it splinters (though the latter can be part of the evolution of a CoP and a social learning system) nor so confined that there is no need for exchange.

-

Learning projects that explore or fill in gaps in the knowledge and practice of a community increase the commitment of participating members.

-

Artifacts produced, gathered and maintained so that they are accessible and useful traces of the community’s activities allow for reflection upon the evolution of the CoP.

Resources

The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences ?Chapters?

Bruckman, A. (2006). Learning in online communities. In R. K. Sawyer (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 461-474), Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Key Works

-

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation.Organization science, 2(1), 40-57.

-

Etienne, W., MacDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business Press.

Successful Examples

-

Technology for Communities project (A good collection of software tools used by COPs)

References

-

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge university press.