Assessment and Learning

Purpose of assessment (Major Tab 1)

To select or to learn?

This question sounds commonsensical, however, deep reflection on this fundamental issue sharpens our design and use of assessment in classroom in order to help students learn effectively.

To select:

- The most obvious reason for the need of assessment is to select. This assumes that students have relatively fixed abilities, and we need to design measures to order, rank or even screen them normally for various administrative reasons.

- The purpose of screening and selecting is of particular importance in educational context where resources are scarce (limited seats for awards, university seats, scholarship, career opening etc.)

To educate:

- Given the overwhelming nature of competition for places and resources, assessing for educating and learning has become a hidden virtue if it has not been completely forgotten. Using assessment to educate and help students learn assumes that students ability can be changed through engaging into meaningful assessment tasks.

- The purpose of using assessment to educator therefore is for monitoring learners’ learning progress, looking for evidences and feedback to help learners to attain learning goals.

In reality, both purposes of selecting and educating are of equal importance. However, it seems that much pedagogical attention has been paid to prepare students for public examinations or high-stake assessments, and as a result, the notion of using assessment to help students learn has been overlooked.

Why is that assessment is important for learning?

Regardless of which purpose of assessment we subscribe to, there seems to be a general consensus among scholars in the area that the design and demand of assessment defines the actual curriculum that students learnt.

- “From our students’ point of view, assessment always defines the actual curriculum.” (p. 187. Ramsden, 1992)

- “Students learnt what they think they will be tested on…Students’ understandings take the form they think will suffice to meet the assessment requirements” (p.141. Biggs, 2002)

- “The tendency in course examination is to pose the question “How much do you remember of what has been covered?” rather than “What can you do with what have learnt” (p.208. Dressel, 1976)

It is why the understanding of the design of assessment is essential for enhancing learning quality and outcomes.

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Basic concepts about assessment (Major Tab 2)

We have discussed the purpose of assessment, assuming that we all have a clearly shared definition. But what is ‘assessment’ and how does the term differ from ‘measurement’ and ‘evaluation’ that are often used interchangeably with assessment? Are they the same?

Assessment, Measurement and Evaluation:

- “Assessment is the process of obtaining information that is used to make educational decisions about students, to give feedback to the students about his or her progress, strengths, and weaknesses, to judge instructional effectiveness and curricular adequacy, and to inform policy.” (American Federation of Teachers, National Council of Measurement in Education, and National Educational Association, 1990, p.1)

- “Measurement is the process of converting information into a numeric representation and quantification of an educational event” (McMillan, 2001).

- “Evaluation is the process of educators make specific judgments or decisions based on the use of various forms of assessment, therefore, evaluation is an interpretation of assessments.” (Stiggins, 1993)

In sum, the term ‘assessment’ is the most encompassing, which includes both the process of ‘measurement’ and ‘evaluation’. Assessment are sometimes used to serve different purposes, based on the measurement information gathered as well as the interpretation of such measurements.

Essential concepts on assessment (apply to all types of assessment)

No matter which purpose we design our assessment for, there are some essential concepts that we need to understand in order to ensure the assessment produce meaningful information for use.

Validity

It represents the appropriateness and suitability of assessment practices, specifically in relation to the interpretations and applications of resulting data. It simply asks the question whether the measurement measures the thing we aim at measuring.

Some guidelines for safeguarding validity:

- Carefully specify the content of task to be assessed

- Consider the cognitive and affective processes involved in task performance

- Compare the scores between groups

- Analyze score that occur before and after relevant educational experience or intervention

- Compare the scores to those for related measures

Reliability

It represents the stability and consistency of assessment outcomes. It simply asks the question whether the measurement can produce similar range of measurement when applied more than once.

Common forms of assessment

Selected -response item:

Assessment form that requires students to choose an answer from among given options (multiple-choices, true-or-false, matching), which normally involves three components:

- Stem: the basic statement of the question

- Response options: All the potential answers to the posed question or incomplete statement

- Distracter: Some potential answers as response options that have the power to differentiate students from misunderstanding of conceptions

The pluses of this form of assessment

- Easy to score

- Tend to have high reliability and validity

- Ready for potential standardized procedure

- Allow for breadth of coverage

The pitfalls of this form of assessment is:

- Hard to construct good item

- Emphasis on only one correct answer

- Result in highly contrived and superficial conception of learning

- Overlook other aptitudes or abilities

- Influenced by students test-taking strategies

Guidelines for constructing better selected-response items:

1) Multiple-choice:

- Keep the problem statement simple and clear

- Remove any unnecessary clues in stems and options

- Be sure the distracters are sufficiently distracting

- Avoid unnecessary confounds (e.g. option such as ‘none of the above’; ‘all options except’)

2) True or false:

- Ensure that the problem statements are complete, clear and precise

- Avoid absolute and universal words unless it is necessary (e.g. always, never, every, all)

- Consider highlighting key words or phrases for young and novice students

- Give students the chance to explain their decision and reward marks partially

3) Matching:

- Provide sufficient imbalance between stems and response options

- Be certain that stems and options fit together unambiguously

- Select stems and options from the same category of information

Constructed-response item:

Assessment form that requires students to compose an answer instead of selecting from specified options. It can be in restricted (fill-in the blanks, short answers) or extended form (essay writing)

The pluses of this form of assessment:

- Opportunity to explore a topic in depth

- Value higher-order thinking skills, such as integration, synthesis

- Possibility for partial reward

- Possibility for multiple correct answers

The pitfalls of this form of assessment:

- Confounded by language proficiency

- Potential for scoring bias

- May have lower reliability

Guidelines for constructing better constructed-response items:

1) Fill-in-the-blanks:

- Formulate root statements that are self-contained

- Target declarative information that can be specified in a word or two

- Put the missing terms at the end of the sentence to avoid ambiguity

- Provide blanks of consistent and adequate length

- Eliminate unnecessary textual clues

2) Short answers or essay type questions:

- Target higher-order skills

- Provide sufficient information for students to expect scope of responses

- Pre-establish criteria for evaluation and share with students

- Score each questions separately and blindly

Section adapted from Alexander, P. A (2006), Psychology in Learning and Instruction

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Forms and purpose of assessment (Major Tab 3)

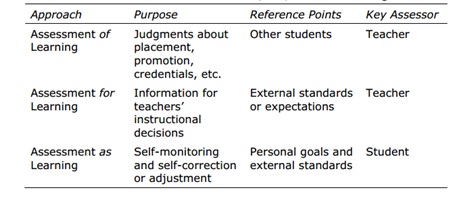

Assessment can be generally grouped under the following forms by their major purpose:

Assessment of Learning (Summative assessment):

- Carried out at the end of the course/project, semester or year typically used to assign a course grade for some terminal decision regarding students or instruction.

- It is assessment used to confirm what students know, to demonstrate whether or not the students have met the standards and/or show how they are placed in relation to others.

- In assessment of learning, teachers concentrate on ensuring that they have used assessment to provide accurate and sound statements of proficiency or competence for students.

- Both teachers and students are more familiar with assessment of learning, or the mentioning of assessment is automatically equated with it because of the looming demand of benchmarking and accreditation.

- However, educators and researchers question whether the focus on and the frequent use of assessment of learning will foster deep learning; as argued analogously, that whether simply measuring a plant frequently will make it grow.

Assessment for Learning (Formative assessment)

If measuring the learning outcome often does not help our students learn better, there is a need for teachers to use assessment during the process of teaching and learning in such a way to inform instructional practices and hence foster effective learning among students, this is what we called ‘Assessment for Learning’ (or formative assessment).

- Carried out along the process of a course. It is performed in the form of feedback by a teacher for the purpose of monitoring progress so that needed modification can be incorporated in future instruction. It marked by the practice of using the assessment evidences to guide and adapt the teaching work to meet students’ needs so as to improve the learning quality

- The emphasis is on teachers using the information from carefully-designed assessments to determine not only what students know, but also to gain insights into how, when, and whether students use what they know, so that they can streamline and target instruction and resources.

- In a nutshell, researchers and educators agree with the following definition of Assessment for Learning:

“It is the process of seeking and interpreting evidence for use by learners and teachers to decide where the learners are in their learning, where they need to go and how best to get there.” (Broadfoot, Daugherty, Gardner, Harlen, James, & Stobart, 2002 pp.2-3).

Seven percepts that summarized the characteristics of formative assessment or Assessment for Learning (Broadfoot et al, 2002)

Researchers highlight some of the key characterisitcs in the use of Assessment for Learning in classroom, they are:

- It is embedded in a view of teaching and learning of which it is an essential part;

- It is involves sharing learning goals with students;

- It aims to help students to know and to recognize the standards they are aiming for;

- It involves pupils in self-assessment;

- It provides feedback which leads to students recognizing their next steps and how to take them;

- It is underpinned by confidence that every student can improve;

- It involves both teacher and students reviewing and reflecting on assessment data.

Assessment as learning:

Among the key elements in Assessment for Learning, there is always a dimension of involving students to understand, monitor and evaluate themselves and their peers with explicit criteria and standards. Researchers (Lorna, 2003) further differentiated this group of assessment that emphasizes the development of students’ metacognitive ability, naming it “Assessment as Learning”.

- Carried out along the process of a course and is performed in forms of activities and tasks monitored by students and peers, in such a way students learn through the process the assessing oneself and assessing their peers.

- However, assessment as learning emphasizes using assessment as a process of developing and supporting metacognition for students. It highlights the importance of self- and peer- assessment.

- It focuses on the role of the student as active, engaged and critical assessors make sense of information, relate it to prior knowledge, and use it for new learning. The process develops students’ metacognitive ability.

“For students to be able to improve, they must develop the capacity to monitor the quality of their own work during actual production. This in turn requires that students possess an appreciation of what high quality work is, that they have the evaluative skill necessary for them to compare with some objectivity the quality of what they are producing in relation to the higher standard, and that they develop a store of tactics or moves which can be drawn upon to modify their own work.” (Sadler, 1989)

Summary of the purpose and key assessors in three different forms of assessment:

Extracted from Lorna, E (2003). Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximize Students’ Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA. Corwin Press.

Information extracted from “Rethinking Classroom Assessment With Purpose in Mind Assessment for Learning Assessment as Learning Assessment of Learning” (2006) Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education www.wncp.ca.

Resources:

http://www.highland.gov.uk/learninghere/supportforschoolstaff/ltt/issuepapers/peer-selfassessment.htm

Video: http://www.edugains.ca/resourcesAER/PrintandOtherResources/EarlVideo/index.html?movieID=1

Assessment Toolkit (extracted from “Rethinking Classroom Assessment With Purpose in Mind Assessment for Learning Assessment as Learning Assessment of Learning” (2006) Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education www.wncp.ca.)

The use of Assessment for Learning and Assessment as Learning can take many forms. The most common one is through asking students’ questions. However, instead of repeatedly asking student questions, it would be helpful to have a variety of activities to select from in order to keep your student engaged and to cater for different learning and curriculum needs.

The following are an non-exhaustive list of small activities, derived from the principle of Assessment for Learning (and Assessment as Learning), for your adoption or adaptation in classroom practices:

Tasks for gathering information:

- Questioning: asking focused questions in class to elicit understanding

- Observation: observing students systematically as they process ideas

- Homework assignments: eliciting understanding with extended time to work on

- Learning conversations or interviews: investigating discussions with students about their understanding and confusions

- Demonstrations, presentations opportunities for students: allowing students to show their learning in oral and media performances, exhibitions

- Quizzes, tests, examinations opportunities for students: allowing students to show their learning through written response

- Rich assessment tasks complex tasks: encouraging students to show connections that they are making among concepts they are learning

- Computer-based assessments: Using software applications connected to curriculum outcomes systemically and purposefully

- Simulations, docudramas simulated or role-playing tasks: encouraging students to show connections that they are making among concepts they are learning

- Learning logs descriptions: providing opportunities for students to maintain the process they go through in their learning

- Projects and investigations opportunities for students: showing connections in their learning through investigation and production of reports or artifacts

Interpreting information:

- Developmental continua profiles: describing student learning to determine extent of learning, next steps, and to report progress and achievement

- Checklists descriptions of criteria: understanding students learning

- Reflective journals reflections and conjecture: maintaining about how students’ learning is going and what they need to do next

- Self-assessment process: students reflecting on their own performance and use defined criteria for determining the status of their learning

- Peer assessment process: students reflecting on the performance of their peers and use defined criteria for determining the status of their peers learning

Record-keeping:

- Anecdotal records: providing focused, descriptive records of observations of student learning over time

- Student profiles: providing information about the quality of students work in relation to curriculum outcomes or a students individual learning plan

- Video or audio tapes, photographs visual or auditory images: providing artifacts of student learning

- Portfolios: demonstrating accomplishments, growth, and reflection about their learning through a systematic collection of work throughout the course

Communicating:

- Demonstrations, presentations formal student presentations: showing their learning to parents, judging panels, or others

- Parent-student-teacher conferences: providing opportunities for teachers, parents, and students to examine and discuss the students learning and plan next steps

- Records of achievement: showing detailed records of students accomplishment in relation to the curriculum outcomes

- Report cards: showing periodic symbolic representations and brief summaries of student learning for parents

- Learning and assessment newsletters: giving routine summaries for parents, highlighting curriculum outcomes, student activities, and examples of their learning

Taking Stock: Is this Formative Assessment? How can I tell?

- Though one of the key difference between Formative and Summative assessment is regarding the time of use (during vs. at the end of the course) and the possible format (open-ended work vs. examination).

- However, relying on these two differences may have over-simplified the pivots of formative assessment, and sometimes differentiating summative from formative assessment can be tricky.

- Try to differentiate the following scenarios and come up with rationales for your answers. See how far you have grasped the idea of Formative Assessment!

Scenario One

Teacher in a physics class, asks students to show ‘yes’ or ‘no’ cue cards, to decide the class’ prior knowledge in the topic.

Scenario Two

An English teacher asks students to keep a Portfolio of all their draft writings and only the final submission of the writing will be graded.

Scenario Three

A team of mathematic teachers hold a review meeting of their subject, and collectively reflect on their teaching with the use of last year students’ final examination performances to decide which module requires more pedagogical attention and time. Teaching plan and alloted time for the topic has then be subsequently changed in next year to address that need.

Answers and explanations

The above three scenarios demonstrate several over-simplified views of what is regarded as Assessment for Learning:

(It’s common to say 2) is the only example of Assessment for Learning. But in fact, both 1) & 3) are Assessment for Learning, except 2). WHY?)

- Scenario One is only an example of class activities that engage students, and such deviates very much from the idea of ‘assessing’ students. It cannot be Assessment for Learning.

- Scenario Two is using the very catchy educational buzzword ‘portfolio’ which implies on-goingness of students’ work, so it must be Assessment for Learning.

- Scenario Three involves examination, which takes place at the end of the semester, it is summative in nature, it’s a type of Assessment of Learning, and cannot be Assessment for Learning.

If the above reasoning is close to your way of justifying your answers, here we are tackling the key misconception of what is and what is not Assessment for Learning.

The idea of using assessment as a source of feedback to guide both teacher’s instructional practices and student’s learning lies at the heart of Assessment for Learning.

So don’t be misled by form of activities or eye-catchy assessment form to decide whether it is Assessment for Learning:

- o Scenario 1, employs strategies to have a quick survey of students’ understanding, and that is used to guide teacher’s teaching of the concept, therefore it is Assessment for Learning, though it doesn’t look like a ‘traditional’ sense of assessment.

- o Scenario 2, we are uncertain, as despite all drafts are kept in the portfolio, there is no information suggested that either students or teachers used any of those information to guide and further improve their learning and teaching. Simply keeping all records of draft does not help learning.

- o Finally, Scenario 3, the team of teachers is using examinations performance systematically to guide their future teaching in hope of improving students’ learning, so it is a form of Assessment for Learning (with summative assessment). It demonstrates the non-exclusivity between summative and formative assessment, which is a common misconception.

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Paradigm of assessment for the demand of the 21st century (Major Tab 4)

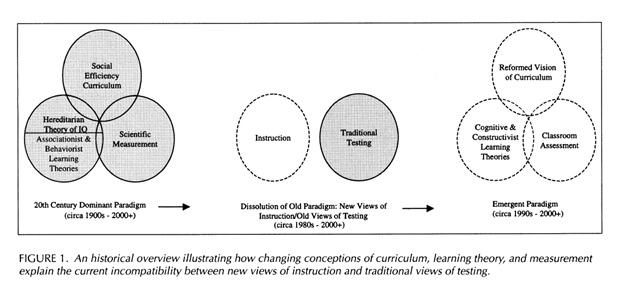

According to Shepard (2000), the role of assessment is closely tied with the paradigm of learning, where previously a behaviorist approach was used and currently a socio-constructivist approach is espoused. Such change in paradigm has huge implication not just in curriculum design but also in classroom assessment.

Diagram extracted from Shepard (2000), The role of assessment in learning culture, 29, 4-14.

From 1980 to 2000:

Previously from years 1980 onwards, educators predominantly assumed a behaviorist paradigm that pertains to the following key assumptions of learning and assessment:

- Learning happens by accumulating bits and pieces of knowledge

- Learning is hierarchically sequenced

- Assessment should be used frequently to ensure mastery of one stage prior to moving on the next

- Assessment is equivalent to learning

- Motivation is extrinsic as it relies on contingency of reinforcement and punishment

From 2000 and onwards:

With the advancement of research and knowledge gained in understanding human learning, it seems that a socio-constructivist paradigm describes better of human learning. Under this paradigm, learning is:

- an active process of mental construction and sense making, in which one’s existing beliefs and knowledge plays a very pivotal role.

- involves more than accumulation of facts but self-monitoring and awareness about when and how to use various strategies to support learning (metacognition)

- the development of expertise in a field as a coherently structured set of principles that represents the way of thinking and seeing, but not merely proper sequencing of events to the highest level in the hierarchy.

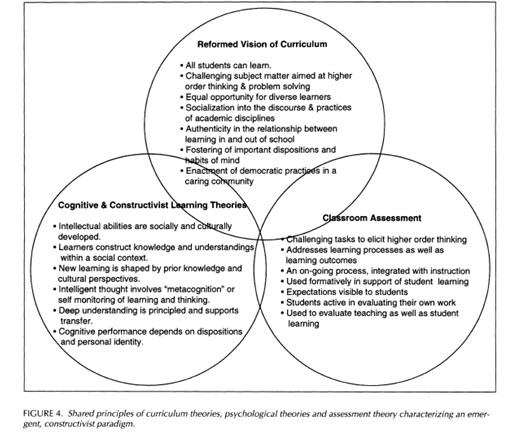

Accordingly to Shepard (2000), assessment has to be changed both in forms and content in order to be compatible with this new paradigm of learning. In particular, Assessment for Learning addresses the need of taking students’ prior knowledge into account; while the use of Assessment as Learning aims at developing students’ metacognition in learning.

How should I implement assessment for learning and assessment as learning in my classroom?

There are many strategies you can use to implement Assessment for Learning and Assessment as Learning in your classroom. You can also use self-developed assessment to cater for similar purposes.

Whichever means you take, the use of Assessment for Learning and Assessment as Learning is more than simply adding a few more activities in your instructional routine, but it is about changing the classroom and learning culture that aligns with the key pivots of how people learn.

Shepard (2000) summarized several principles of using formative assessment to create the necessary classroom culture for sustainable learning (Shepard, 2000):

- On-going assessment: It is the continuous effort use of informal assessment ask in class to assess what a student is able to do independently and what can be done with adult guidance at what degree.

- Assessment of prior knowledge: It is the effort use to tap into students’ existing understanding prior to any instructional exposure. The information can be used to guide instructional practices to best tackle misconceptions

- Teaching for transfer: Robust understanding is signified by the ability to transfer learnt knowledge to wide variety of novel settings. Therefore, there is a need to design assessment that goes beyond familiar contexts and well-rehearsed problems.

- Providing explicit criteria: It is the effort to make students have clear understanding of the criteria by which their work will be assessed.

- Allowing students’ self-assessment: It is the effort to allow opportunities to evaluate their own work with the understood standards and criteria. It increases students’ responsibility for their own learning, furthermore, it helps instilling a collaborative culture of learning between learners and teachers.

Furthermore, in the following diagram, it also helps demonstrate the interrelated dynamics among learning theories (hyperlink to other pages of the site), design of curriculum as well as design of classroom assessment. (Shepard, 2000).

Diagram extracted from Shepard (2000), The role of assessment in learning culture, 29, 4-14.

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Pellegrino, W., Chudowsky, N & Glaser, R. (2001). Knowing what Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment. National Research Council.

- Pellegrino, W., Wilson, M. R. Koenig, J.A. & Beatty, A.S. (2014). Developing Assessment for Next Generation Science Standards. National Research Council.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Choice of assessment and its implication (Major tab 5)

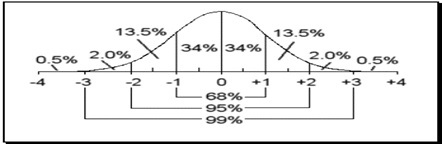

Norm-referenced grading

The grade is determined in comparison with the other students in the group following a more or less normal distribution

The use of summative assessment is normally associated with the use of norm-referenced grading as such can help making fine discriminations among students’ performance

There are several disadvantages:

- It cannot provide an absolute standard of the students (e.g. How does a mark of 84 tells a student regarding how much he or she has attained a certain intended learning outcome? And how can the mark inform both the teachers and students to improve?)

- It involves an arbitrary choice of standards

- Individual performance relies on collective performance which makes comparability across cohorts impossible

- Differential importance of mark (e.g. Why is that the one mark from 50 to 49 (if passing mark is 50) is more important than the one from 90 to 89)?

- The standard for assessment is often unclear to students because it depends on cohorts’ performance and such changes across years.

Criterion-referenced assessment

The grade is determined by the reaching of a set of pre-set criteria and standards. In such case, the number of students able to obtain any of the grades is not fixed and independent from the performance of other students.

The use of formative assessment is normally associated with the use of criterion-reference assessment. As it involves the following steps which lie close to the heart of formative assessment:

- Define Intended Learning Outcomes

- Develop clear & explicit criteria and standards that reflect the attainment of the intended learning outcomes for grading each assessment task

- Communicate explicitly these criteria and standards to students before the grading of students work

- Comment or grade students work based on this pre-determined criteria and standards in order to help students to improve and get closer to attain the intended learning outcomes

Self-referenced grading

Self-reference grading is done with students’ performance as a baseline for comparison. The goal is to track students’ development in a particular learning goal and hopefully to motivate students to improve without having the distraction of ranking and grading.

Reflection

- With this definition, how can the use of CRA counteract some of the pitfalls as identified in the use of NRA?

- If CRA sounds more sensible, why is that in most situation we use NRA? Practically, any shortcoming associate with the use of CRA?

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Designing rubrics (Major Tab 6)

A rubric is a matrix of criteria and standards defined clearly for the purpose of comment or grading students’ work in a qualitative manner. It normally involves an ordered set of verbal performance descriptions of criteria and associated standards (Andrade, 2000; McMillan, 2001):

- Criteria involves defining the quality or attributes you are looking for in students work

- Standards involves the indicators to differentiate students performance levels at each of the identified criteria

What are the different types of rubrics?

- Analytic rubrics: Criteria are specified as indicative of each level of performance. (insert example)

- Holistic rubrics: It treats together the various criteria that involve in the piece of assessment. As a result, the description accompanying each score level addresses multiple criteria. (insert sample rubrics from website)

- Essay writing

- Engineering project on thermodynamics

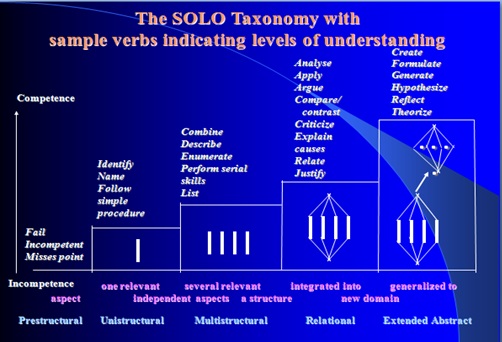

Is there any generic framework for criterion-reference grading? What is SOLO taxonomy?

Structure of the Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) and assessment is based on the level of learning complexity (Biggs, 1999). It provides a generic standards that can be applied in different domain of knowledge and assessment work forms.

In SOLO, there are five levels, in ascending order they are:

- Pre-structure: The task is engaged, but the learner is distracted or misled by an irrelevant aspect belonging to a previous stage or mode.

- Uni-structural: The learner focuses on the relevant domain and picks up an aspect to work with.

- Multi-structural: The learner picks up more and more of the relevant features, but does not integrate them together.

- Relational: The learner integrates each parts with each other, so that the whole has a meaningful structure and meaning.

- Extended abstract: The learner generalizes the structure to take in new and more abstract features, representing a higher mode of operation.

SOLO in graphical representation (extracted from Biggs and Tang’s presentation, 2009). Source: http://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Relationship of curriculum and assessment (Major Tab 7)

How should I start planning the curriculum and assessment in my subject?

In order to design assessment to promote effective learning, according to Biggs (1999), we should understand that the key in teaching is not what teachers teach but what teacher would like the students to learn and how to help them achieve that. And such involves attention in the following aspects of curriculum and assessment design:

- To consider and define the intended learning outcomes for students

- To clearly articulate and share the intended learning outcomes with students

- To design assessment tasks as well as learning processes that strategically align with these identified intended learning outcomes.

- To provide feedback to help students close the gap between their actual performance and the intended learning outcomes.

In a nutshell, Biggs named the process “Constructive Alignment”.

What is Constructive Alignment (CA)?

- “Constructive” refers to students’ active construction of meaning through relevant and aligned learning activities and assessment tasks

- “Alignment” refers to a learning environment where teaching and learning activities and assessment tasks are aligned to the intended learning outcomes of a subject.

A good teaching system aligns teaching method and assessment to the learning activities stated in the objectives, so that all aspects of this system are in accord in supporting appropriate student learning. This system is called constructive alignment, based as it is on the twin principles of constructivism in learning and alignment in teaching. Biggs (1999). Teaching for Learning at University. OUP

The alignment between the selection of assessment and intended learning outcomes creates “backwash effect” in learning.

What is backwash effect?

It refers to the outcome of how assessment determines the actual curriculum students learnt. So, there can be good or bad backwash effect depending on the alignment or misalignment between assessment and curriculum.

Positive backwash effect

- When assessment is used to align well with the curriculum and the intended learning outcomes, it provides positive desirable effect on learning.

- Case 1:

In a Psychology Research Method course, the intended learning outcome is to help students able to conduct small scale empirical study. One major assessment tasks in the course therefore requires students to replicate famous psychological experiment by collecting small sample of data and producing a final report that abides to APA format.

Negative backwash effect

- When assessment is designed in a way that doesn’t reflect or align with learning outcomes, it produces null or sometimes even adverse effect on learning.

- Case 2:

In an Product Engineering course, the intended learning outcome is to help students to be able to design and construct a novel product to solve problem faced by people in the industry. One major assessment task is final examination, in which it contains MCQ and some open-ended questions asking knowledge and issues in relation to quality of good product design and defining the logistic of product design.

Reflection

- What are the features in the assessment task in Case 1 that would likely to help reinforcing the intended learning outcomes?

- What kind of outcome will the assessment tasks in Case 2 likely to reinforce? Why?

- What other alternative assessment tasks can be used in Case 2 would be more likely to align with the intended learning outcomes and therefore bring about positive backwash effect? Why?

- How does the understanding of backwash effect help us to reflect on design and demand in some of the local public examination format and questions? What kind of outcomes will they reinforce?

After understanding the key idea of Constructive Alignment and backwash effect, it is essential for us to know two key forms of assessment: Summative Assessment (Assessment of Learning) and Formative Assessment (Assessment for Learning)8. How to establish an assessment culture? What do teachers need to know about assessment?Authentic incorporation of Assessment for Learning (formative assessment) practices in classroom requires more than effort in simply adding a few activities in the existing teaching plan.

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

Creating an assessment culture in your classroom (Major tab 8)

Authentic incorporation of Assessment for Learning (formative assessment) practices in classroom requires more than effort in simply adding a few activities in the existing teaching plan.

It requires the change of teachers’ beliefs regarding learning and teaching in order to incorporate assessment as an integral part of the learning process. It requires some structural and conceptual change of pedagogy. However, such change and use is advised to be taken on board gradually (Black & William, 1998; Shepard, 2000).

With the introduction of different theories, concepts and ideas regarding assessment in classroom, it is hoped that teacher should be able to:

- Choose assessment methods appropriate for instructional decisions

- Develop assessment methods with principles that align with the latest learning paradigms and that are appropriate for instructional decisions

- Use assessment evidences and results to make decisions about individual students, planning instruction, developing curriculum and targeting school improvements

- Communicate assessment criteria, standards and results to students, parents and other lay audiences in a highly explicit and intelligible fashion

Useful Websites

- EDB sites on AfL

- Succinct guide on using AfL to develop higher-order thinking

- Ideas hub for AfL

- Example for an English Curriculum

- AfL in UK

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction. Pearson Education.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning in University. Open University Press.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5, 7-71.

- Black, P. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting into Practices. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4-14.

- Slavin, J., Ysseldyke, J. E. & Bolt, S. (2007). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education (10th Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company. Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.

- Woolfolk, A.(2014). Educational Psychology (12th Ed). Pearson New International Edition.